- The Monopoly Report

- Posts

- The Flywheel of Google Remedies

The Flywheel of Google Remedies

Round and round - I knew right from the beginning, that you would end up winning.

I’m Alan Chapell. I’ve been working as outside privacy and regulatory counsel at the intersection of privacy, competition, advertising, and music for decades, and I’m now a regulatory analyst writing for The Monopoly Report and The Chapell Report regulatory outlook.

The Monopoly Report podcast is out! Listen in as Dr. Gabriela Zanfir-Fortuna discusses the EU’s attempt to upend data protection rules via the Digital Omnibus proposal.

Someone went to EDVA, but all I got was a Prebid T-shirt

Let me start by applauding the fantastic coverage of the Google antitrust trials by Arielle Garcia and Ari Paparo. If you want the details on closing arguments in the Google adtech trial, you should check out their work. I’m not going to try to restate it all here.

I acknowledge that we’re all reading tea leaves at this point. Judge Brinkema's questions during closing arguments suggested more than a wee bit of skepticism about the commercial viability of divestiture of AdX given the certainty of a lengthy appeal by Google. As a result, many believe that the most likely outcome is for the judge to rule in favor of a slate of behavioral remedies.

That outcome might also represent a nail in the coffin of the antitrust’s era of good feelings – and an admission that existing antitrust law is not fit to address the complex, vertically integrated technology platforms operated by Big Tech.

I’ve thought a good deal about the questions Judge Brinkema raised. And I have to admit: I can see the logic behind what the good judge characterized as the "commercial reality" of divestiture.

In fact, I’d take it a step further and suggest that there are at least six commercial realities.

The 6 Commercial Realities

Judge Brinkema’s ruling is likely to be guided by the following:

Rapid marketplace change: Judge Brinkema interrupted the DOJ's opening argument repeatedly to express concern about timing, noting that the industry is changing rapidly. And that no one can predict what the market will look like in three to five years.

Alan’s Take: Yep. And if anything, the pace of change has picked up dramatically. It’s one of the things that ultimately doomed the recent FTC case against Meta.

Google has little choice but to appeal the liability decision: Given all of the private antitrust litigation resting at the foot of Judge Brinkema’s liability decision, the only rational choice for Google is to appeal.

Alan’s Take: If the government cases continue to net favorable liability rulings and unfavorable remedies, we’ll see even more private antitrust litigation. But how many of you are confident that you’ll still be in this industry when the Supreme Court finally rules on the Google adtech liabilities in 2034? (I can’t wait to read Justice Aileen Cannon’s analysis).

Structural remedies will take years; behavioral remedies take months: Behavioral remedies could potentially take effect during the appeals process, providing relief after 12-15 months. An order from Brinkema involving divestiture would likely be stayed pending appeal. Given the appeals process will likely take years and if the liability findings are reversed… what benefit would the market gain from a remedy that never took effect?

Alan’s Take: I think the timing narrative is a bit off here. Behavioral remedies will take exactly five years and 11 ½ months to kick in… only to be abandoned at the six-year mark once the monitoring process is complete. Seriously, there’s going to be lots of back and forth on any number of issues, and that’s going to take much longer than 15 months.

Google should be given the chance to make this right: The judge has repeatedly noted that courts are supposed to give the monopolist the benefit of the doubt and that behavioral remedies deserve a chance to prove effective before resorting to structural intervention.

Alan’s Take: Personally, I find it odd that the evidentiary shenanigans engaged in by Google don’t seem to have much weight here, as evidence spoilation goes to the heart of whether or not Google could and should be trusted by the court. There are enough examples of Google to have played games in this and other forums. It’s hard to rationalize why they’re being given benefit of the doubt here. Such is life in the antitrust world.

Government has no clear divestiture plan: The lack of an identified upfront buyer and concrete divestiture plan creates practical obstacles to structural relief. Moreover, the chances are that any potential buyer will be large enough that the sale would raise its own level of regulatory scrutiny, which will cause further delays. Judge Brinkema needs to issue an order that is specific and enforceable. Ordering Google to divest AdX without clarity about transaction structure, buyer qualification criteria, or regulatory approval processes leaves too many questions unanswered. And open questions cost time.

Alan’s Take: Lots of folks speculated about a number of potential buyers of AdX. The fact that the DOJ apparently wasn’t able to point Judge Brinkema to one of them speaks volumes.

Unintended consequences of divestiture: Google’s super lawyer Karen Dunn offered a number of points about the unintended consequences of divestiture, such as: (a) divestiture would include video and mobile ads not part of the monopoly findings, (b) that 92% of publishers receive Google Ad Manager for free with no guarantee about what happens to them post-divestiture, and (c) that there's no assurance a buyer would maintain current service levels to publishers.

Alan’s Take: Agreed that these are issues to be addressed. But let’s not pretend that we have any assurances from Google re: (b) or (c). And (a) sounds more like a Google problem than a reason not to move forward with divestiture.

Too Big to Breakup?

All of the above points beg a really important question: If divestiture is not appropriate in this case for the reasons stated above, then when exactly is it appropriate?

It is almost impossible to envision a scenario today where the commercial realities enumerated above don’t apply to a case brought against a Big Tech platform. At some point, we’re effectively removing divesture from the list of available remedies to antitrust problems for Big Tech.

The DOJ's Matthew Huppert touched upon this outcome in his closing argument. For antitrust laws to continue protecting markets, courts cannot accept that complexity confers immunity.

What’s worse: The commercial realities analysis doesn’t really capture the futility of behavioral remedies. Buying into the premise requires one to believe that publishers are better off with half a loaf today as opposed to nothing (or next to nothing) years down the line. And if you frame it in those terms, then Judge Brinkema’s logic makes sense.

The trouble is: I’m not sure there’s even half a loaf to be had here.

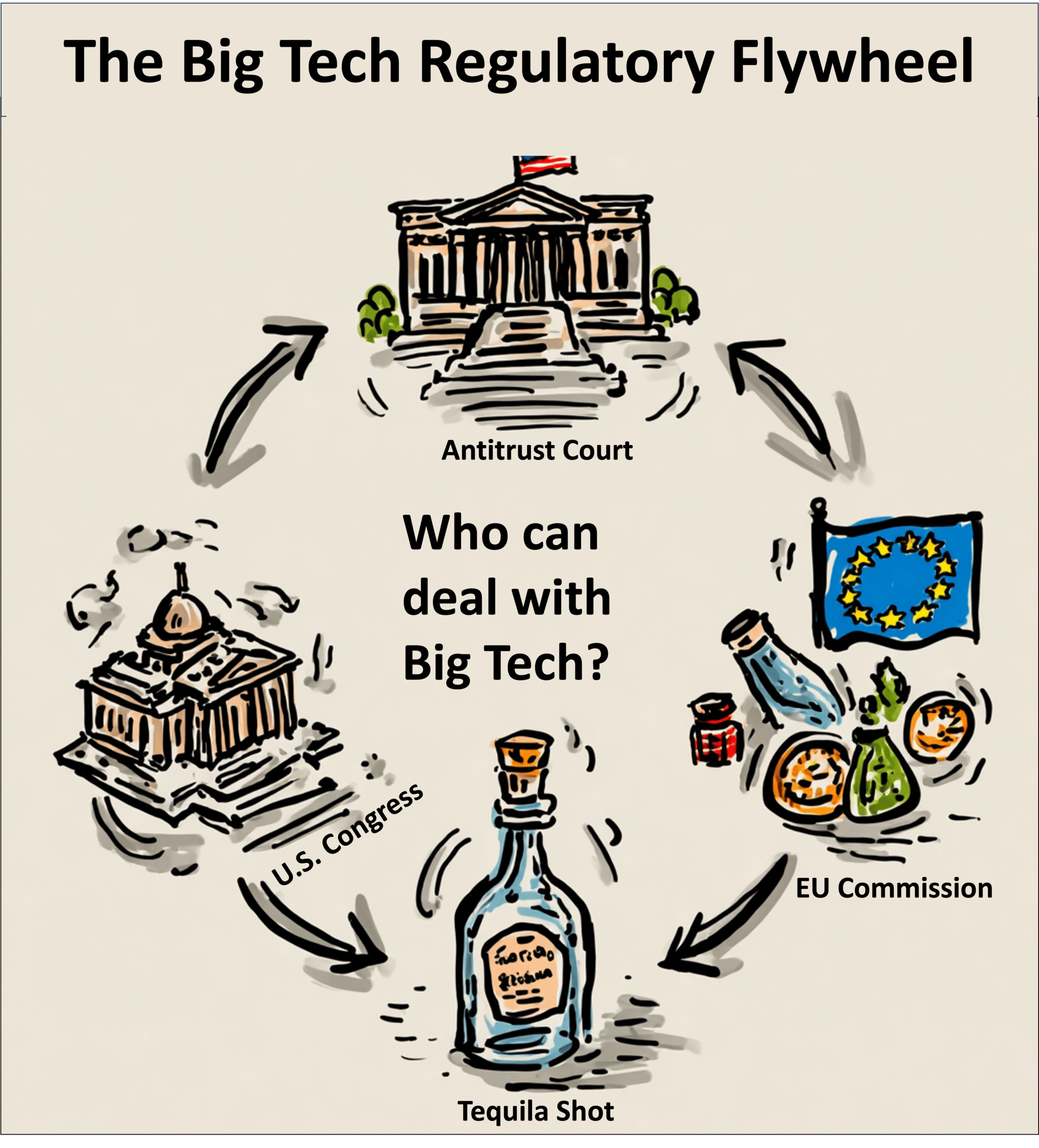

The Regulatory Flywheel

And if antitrust law won’t rein in big tech, who or what will?

The U.S. Congress?

The EU Commission?

An act of god?

Round and round the flywheel goes. As spoken by the great philosophers of hair metal:

I knew right from the beginning,

That you would end up winning.

Marketecture Live III

Marketecture Live is going BIG with our new partners: Adweek and TVREV.

Marketecture Live III: Consumers in Control takes place on March 10-11, 2026, at the Glasshouse in NYC.

2 Full Days

3 Tracks

1,000+ Attendees

Celebrity Speakers

If there’s an area that you want to see covered on these pages, if you agree/disagree with something I’ve written, if you want tell me you dig my music, or if you just want to yell at me, please reach out to me on LinkedIn or in the comments below.

Reply